Building a Soil Data Ecosystem: Africa Steps Forward on Fertilizer and Soil Health Challenge with Multi-stakeholder Approach

Workshop participants at the CIFOR-ICRAF Nairobi campus

Regional leaders, scientists, policymakers, and development partners gathered at the ICRAF Campus in Nairobi on January 27–28, 2026 for the inception workshop of a groundbreaking initiative: Establishing an ecosystem of soil data-driven services to meet the Global Fertilizer and Soil Health Challenge. The workshop was anchored in the three‑year project titled “Establishing an Ecosystem of Soil Data-Driven Services to Meet the Global Fertilizer and Soil Health Challenge.” The initiative is implemented by CIFOR-ICRAF and the Coalition of Action for Soil Health (CA4SH) in collaboration with the Varda Foundation, with financial support from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD). It builds on a soil knowledge exchange pilot conducted in 2024 in Kenya and Tanzania, which identified key barriers and opportunities for strengthening collaborative soil data ecosystems

The collaboration with multiple stakeholders from Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and Tanzania, aims to transform soil health management through knowledge exchange, open data and innovative digital platforms.

Phillip Osano, COO of CIFOR-ICRAF, gave welcoming remarks, highlighting the urgent need to connect soil science with local realities, strengthen national decision-making, and bridge the gap between policy and practice. He emphasized that healthy soil underpins resilience, productivity and economic stability.

“ Land degradation carries enormous economic costs, and addressing it requires strengthening national planning and decision-making…while creating lessons that can be replicated across Africa.

”

Osano referenced frameworks such as the Kampala Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme (CAADP) Declaration and the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan (AFSH-AP) as evidence of soil health’s centrality to Africa’s development agenda. The Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF) was presented as a tool vital for tracking changes over time, while the SoilHive platform was introduced as a solution for managing soil data locally yet ensuring it remains discoverable and interoperable across countries.

Osano also reflected on the importance of partnerships, noting that collaboration accelerates learning and action. With the International Year for Rangelands and Pastoralists providing a timely backdrop, the workshop highlighted how shared knowledge, co-design and open data could empower farmers, inform national policies, and strengthen food and agriculture systems. The remarks set the stage for building a robust soil data ecosystem that supports both local realities and continental ambitions for sustainable land management and agricultural productivity.

The opening remarks by Geir Arne Schei, Deputy Ambassador, Minister Counsellor at the Embassy of Norway in Kenya, emphasized that food security is a top priority for Norway and closely aligned with the ambitions of the Africa Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan (AFSH-AP). He highlighted the critical role of healthy soil in climate resilience, noting their capacity to store carbon, yet lamenting that few Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) recognize this. Schei stressed the need for collective action to drive change in both policy and practice, grounded in evidence and continuous monitoring.

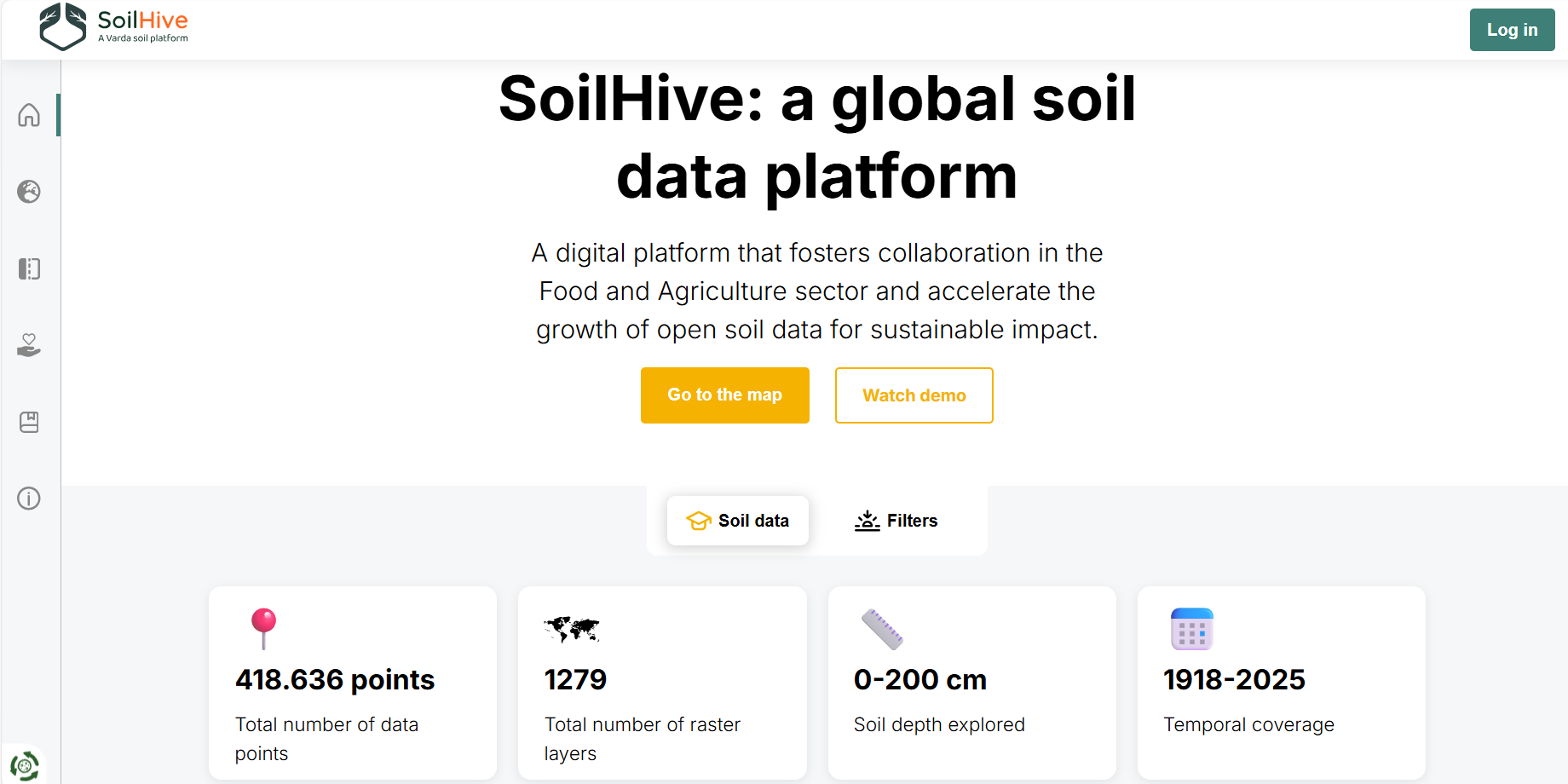

Ingvild Langhus, Senior Advisor for Food Security at NORAD, launched the initiative by underscoring the importance of knowledge exchange, resource efficiency, and treating soil data as a public good. She explained that SoilHive: A platform designed to optimize soil data sharing, ensure transparency through open data and enable interoperability across countries, offered a solution to fragmented data storage by consolidating information into a common, accessible system.

Ingvild Langhus, Senior Advisor for Food Security, NORAD

“This project creates a win-win situation for all stakeholders, from farmers to policymakers, by enabling better decision-making and strengthening national economies.”

Farmers were recognized as key decision-makers whose access to reliable soil data could directly influence productivity and resilience. Langhus also reflected on the co-design process of the platform, referencing a workshop in Rome that emphasized usability and local relevance. She stressed that the platform must be easy to use for those who need it most, while fostering collaboration and new connections among diverse stakeholders.

Together, all these remarks set a strong foundation for the project’s vision: building a sustainable, inclusive and evidence-based soil data ecosystem that supports both local and national economies while advancing Africa’s broader agricultural and food security goals.

INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT

Leigh Winowiecki, Global Research Lead: Soil and Land Health Theme, CIFOR -ICRAF and Co-Lead of the Coalition of Action for Soil Health (CA4SH) passionately introduced the project: Healthy soil is the bedrock of ecosystem services, food security, and climate resilience. Yet, with 65% of farmland degraded across Africa, restoration goals like AFR100 and biodiversity strategies (NBSAPs) cannot be achieved without putting soil at the center. The project is tackling this challenge head-on by transforming fragmented soil data into a shared, discoverable and usable ecosystem.

Dr. Leigh highlighted Africa’s agricultural transformation agenda, the CAADP, as the most transformative agriculture agenda. The CAADP now boasts of having instituted a soil monitoring taskforce and will soon add soil indicators into its reporting criteria.

“We don’t just monitor for the sake of monitoring, we do it to develop evidence. By building an ecosystem of soil data and ensuring this data is not only available but actively used, this project is positioning soil health as a cornerstone of Africa’s agriculture transformation agenda.”

Ester Miglio, Science & Program Manager, Varda Foundation, shared significant strides the project has made, including:

Multi-country technical consultations held in person to align priorities.

Co-development of an open-source roadmap to guide implementation.

Redesign of the architecture and data model for improved usability.

Advances in product and interface design to ensure accessibility.

Stakeholder interviews (17 conducted) to learn from existing soil information systems (SISs), focusing on co-design, governance, and ownership.

This participatory approach ensures the reflection of real-world needs and builds trust among users, while also strengthening evidence-based negotiations and policy development.

Ester Miglio, Science & Program Manager, Varda Foundation

What is SoilHive?

SoilHive is a collaborative digital platform designed to make soil data more discoverable, accessible, and shareable across countries and institutions. The platform is a Varda Foundation product, it serves as a central hub for soil information that is often fragmented across ministries, research centers and projects.

Key Features of SoilHive

Data aggregation: Brings together soil datasets from multiple sources into one interoperable system.

Accessibility: Allows users to browse, search by country or region, and download soil data and documentation easily.

Transparency: Provides visibility into who accesses data and supports restricted sharing when needed, balancing openness with national sovereignty.

Interoperability: Ensures data can be compared and used across countries, supporting regional and continental initiatives.

Usability: Designed with co‑creation workshops to ensure farmers, policymakers, and researchers can use it effectively.

SoilHive is intended to democratize soil data — turning scattered information into a public good that informs farmer decisions, strengthens national policies and supports Africa’s agricultural transformation agenda.

In response to one of the most pressing questions, how the project would address data sharing, Ester highlighted two key approaches:

Emphasis on transparency and sovereignty: Countries retain ownership of their data, with technology embedded in national research centers.

Provision of full visibility of who accesses data, allows restricted sharing when necessary, and ensures users know what is available and where.

The balance between openness and sovereignty is critical for building collaboration while respecting national priorities. Kenya’s national action plan illustrates how the project can align with ongoing initiatives, while also identifying technical data gaps that remain challenging to address.

With this strong base, the project is leveraging proven methodologies such as the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF) to expand soil monitoring across Africa. As the International Year for Rangelands and Pastoralists unfolds, its contribution to understanding landscapes will be vital in placing soil at the center of restoration and agricultural transformation agendas. By ensuring soil data is accessible, interpretable, and actionable, the project is not just monitoring—it is building the evidence base for Africa’s most transformative agricultural and environmental ambitions.

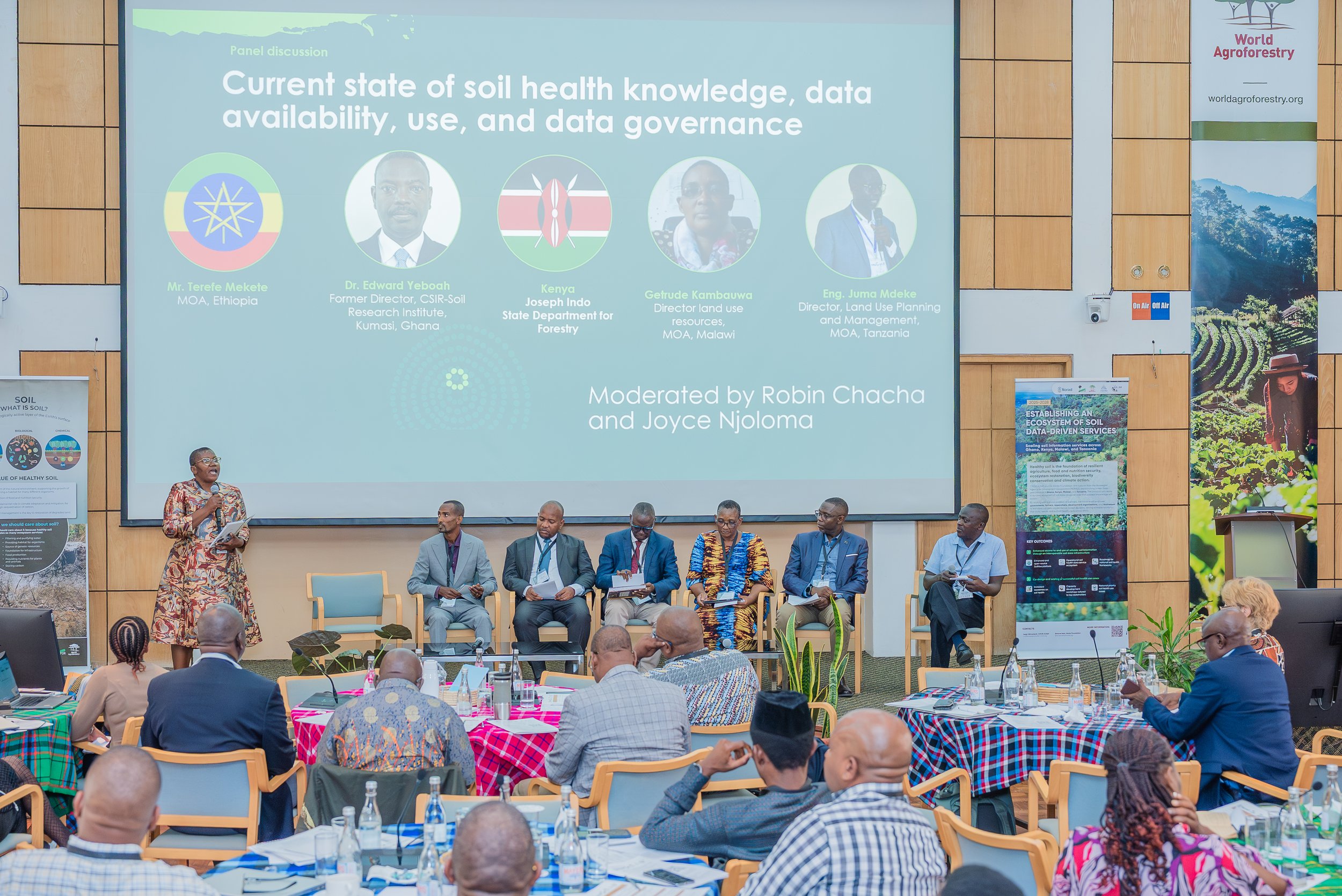

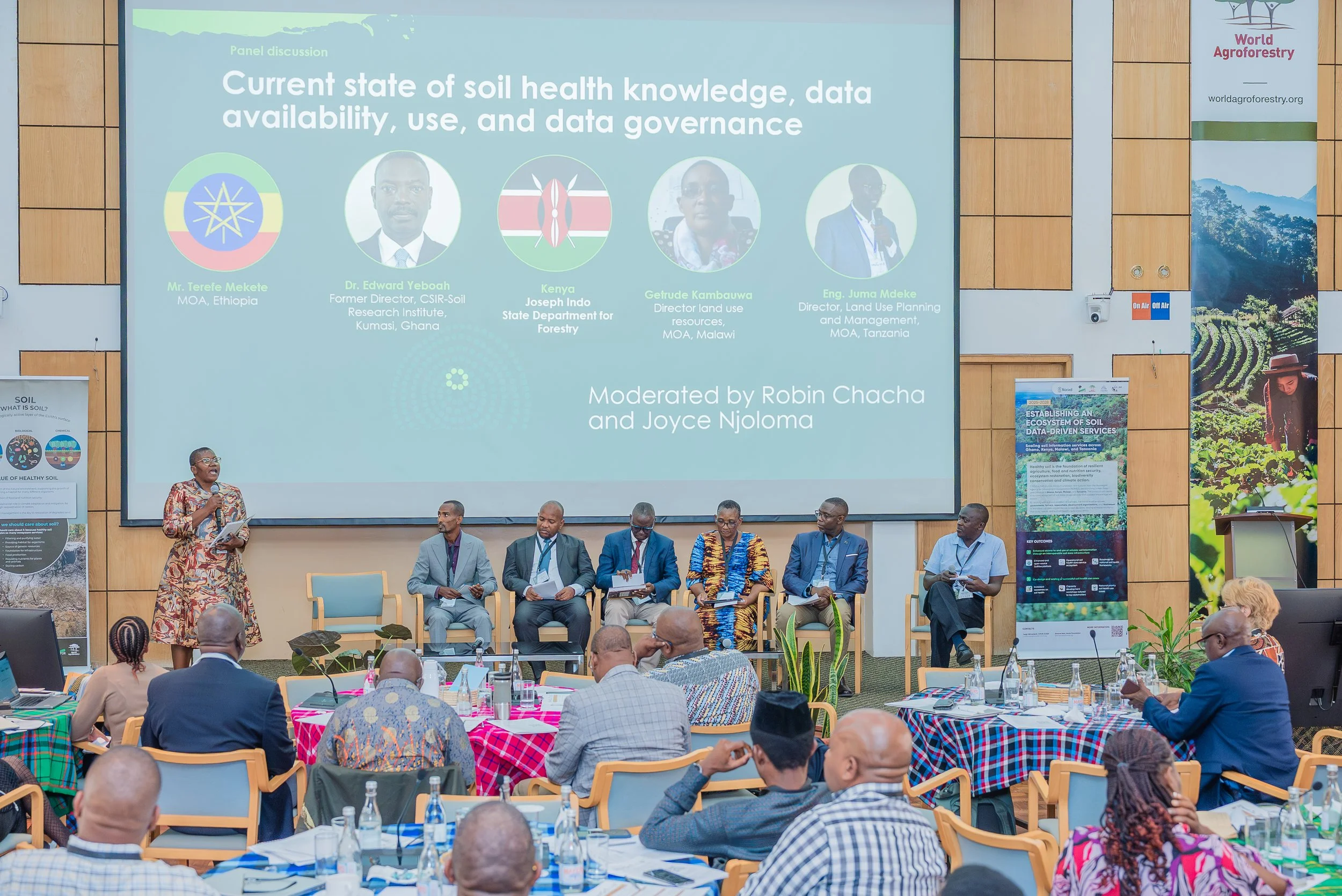

Panel Discussion: Current state of soil health knowledge, data availability and use, and data governance in Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania

The panel brought together representatives from five countries to discuss soil health knowledge, data availability, and governance. Ethiopia was represented by Mr. Terefe Mokete from the Ministry of Agriculture, Kenya by Joseph Indo from the State Department of Forestry, Ghana by Dr. Edward Yaboah from the CSIR‑Soil Research Institute, Malawi by Gertrude Kambauwa from the Ministry of Agriculture, and Tanzania by Engineer Juma Mdeke, Director of Land Use Planning Management at the Ministry of Agriculture. Robin Chacha and Joyce Njoloma from CIFOR‑ICRAF moderated the discussion.

Current State of Soil Data

Across the countries, soil data is generated primarily through research institutions, ministries, and technical working groups. Ethiopia highlighted two types of data delivered directly to farmers via mobile devices. Kenya noted extensive research on soil acidity and nutrient decline, while Ghana emphasized efforts to consolidate fragmented stakeholders through CABI and a technical working group. Malawi reported progress in fertility mapping and area‑specific fertilizer recommendations, though much of the data remains analogue. Tanzania described data collection by research institutions and universities, with projects focused on upscaling soil health and fertilizer production. Collectively, these efforts aim to inform national policies, restoration strategies, and farmer‑level decision‑making.

Challenges and Opportunities

Despite progress, panelists identified common challenges:

Fragmented data systems,

Siloed institutions, that prevents data sharing

Bureaucratic barriers

Limited accessibility for farmers.

Concerns about data ownership

Lack of digitization

Inconsistent storage methods.

Opportunities lie in standardizing data across sources, leveraging national action plans (such as Kenya’s National Action Plan and Malawi’s National Action Plan), and fostering collaboration among diverse stakeholders. By improving governance, accessibility and usability, soil data can become a powerful tool for evidence‑based policy, restoration, and resilience across Africa.

ADVANCEMENTS IN SOIL HEALTH MONITORING AND MAPPING

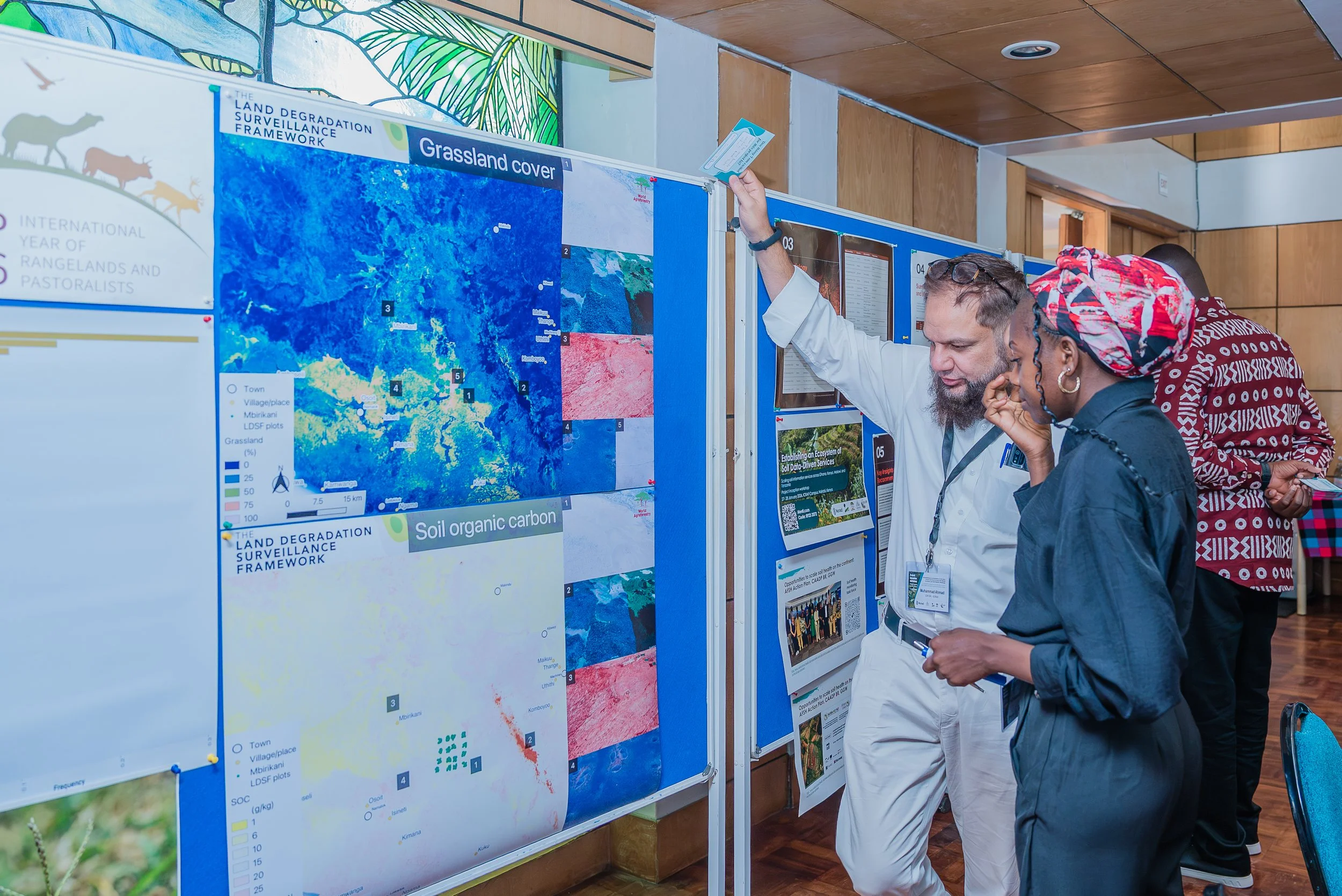

Soil Organic Carbon Maps for Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and Malawi displayed during the workshop

The session on advancements in soil health monitoring and mapping, led by Tor‑Gunnar Vågen and Bertin Takoutsing of CIFOR‑ICRAF, emphasized why monitoring soil health is critical. Reliable data enables farmers to make informed management decisions, supports policy development, and helps understand soil’s role in climate change, drought, and resilience. The presenters stressed the importance of scale and map quality, noting that robust evidence is essential for guiding both local practices and national strategies.

Building on the Land Degradation Surveillance Framework (LDSF), which has sampled over 300 sites across 40 countries, the discussion highlighted scalable and practical approaches to data collection. Innovations such as soil spectroscopy have reduced costs by 90%, making monitoring rapid, accurate and reproducible. Remote sensing technologies—including optical and radar systems—expand the ability to capture land variables beyond soil health.

The call to action was clear: Evidence must not stay in reports—it must shape decisions on the ground, therefore, soil data must be democratized through accessible tools like mobile apps, ensuring it [soil data] informs both policy and practice.

Key Takeaways and Next Steps

Enablers & Barriers: Participants identified skills, infrastructure, and farmer engagement as critical enablers, while siloed institutions, limited connectivity, and lack of farmer and pastoralist involvement remain barriers.

Platform Evolution: Feedback on SoilHive stressed the need for quality control structures and capacity strengthening to ensure sustainability and usability.

Multi‑Stakeholder Dialogue: Governments were urged to create enabling policies, while the private sector’s role in leveraging data for competitiveness was stressed. Partnerships and legal frameworks are essential for sustainable data exchange.

Youth Engagement: Calls to “demystify soil data” for the youth population to ensure young people can understand and apply data directly and to facilitate continuity and sustainability of the project’s vision.

Focal Team: Institution of a team comprising different stakeholders to take the leadership role in the project

Success will be measured by: Accessibility, collaboration, and impact on policy and practice.

YPARD AND #Youth4Soil members with Dr. Leigh Winowiecki

A 12‑month roadmap was outlined, with closing reflections from NORAD’s Ingvild Langhus and CIFOR‑ICRAF’s Christine Magaju reinforcing the vision of soil data as a shared public good.

The inception workshop marked a pivotal step toward building a robust soil data ecosystem in Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Tanzania. By uniting governments, research institutions, development partners, and farmers under a shared vision, the initiative is laying the groundwork for evidence‑based decision‑making, stronger national policies, and resilient agricultural systems. With tools like SoilHive and LDSF, and a commitment to transparency, collaboration, and youth engagement, the project is poised to transform fragmented data into actionable knowledge. As the 12‑month roadmap unfolds, success will be measured not only by improved accessibility and collaboration but by the tangible impact on communities, economies and landscapes.